If you’re a conda user, you may be familiar with the following commands to manage your Python environments:

| |

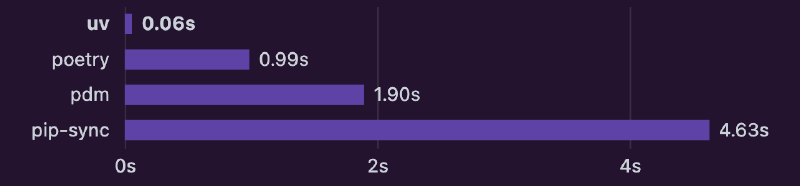

Recently, a new tool uv has emerged that aims to simplify and enhance the management of Python projects. In many cases, it can be a drop-in replacement for conda, providing a more efficient way to handle Python environments and dependencies. There are several blogs and articles that discuss the advantages/disadvantages of using uv over conda, but this post will focus on how to switch from conda/pip to uv with minimal effort.

Contents

conda/pip style usage

If you just want a quick way to use uv like you would with conda or pip, then the following commands should help you get started:

Creating a New Virtual Environment

| |

After running the above command, you will have a ./<myenv> directory containing the new virtual environment. A common convention is to use .venv as the environment name, which can be created with a simpler command: uv venv.

Removing Virtual Environments

As you might have guessed, removing a virtual environment is as simple as:

| |

Activating/Deactivating the Virtual Environment

To activate the virtual environment, you can use:

| |

To deactivate it, simply run:

| |

Installing/Removing Packages

To install Python packages, you can use:

| |

You can check the installed packages with:

| |

Or inspect with:

| |

To remove package(s), use:

| |

[!WARNING] If you are in a uv environment nested inside a conda environment, if you run

pip install <package>, it will install the package in the conda environment rather than the uv environment. If you are in a clean uv environment,pipshould be unavailable, and you should useuv pipinstead.

Packaging and Distributing Your Project

To list all the packages in the environment in a requirements.txt format:

| |

To build a package for distribution, you can use:

| |

This will create a dist directory containing the built package.

To publish your package to PyPI, use:

| |

uv style usage

If you want to take full advantage of uv’s features, you can use it in a more idiomatic way. This workflow revolves around your project’s pyproject.toml file, promoting reproducible environments and clear dependency management.

Creating a New Project

To see the structure of a uv project, the simplest way is to create one:

| |

This will create a new directory called <myproject> with the following structure:

| |

This command sets up a standard, modern Python project structure for you.

What is a Project?

A project is all the files (containing metadata) and directories that are needed to run your Python application. In modern Python, the central piece of metadata is the pyproject.toml file. It declares the project’s name, version, dependencies, and required Python version, replacing older files like setup.py and requirements.txt.

Adding Dependencies

Now you want to add some packages to your project, say numpy and requests. You can do this by running:

| |

After running this command, you will see that the pyproject.toml file has been updated with the new dependencies:

| |

At the same time, uv performs three key actions:

- It creates a virtual environment at

./.venvif one doesn’t exist. - It installs

numpyandrequestsinto the virtual environment. - It creates a

uv.lockfile, which records the exact versions of all installed packages (including dependencies of dependencies).

Note that if you use uv pip install <package>, it will install the package in the current virtual environment, but it will not update the pyproject.toml file or the uv.lock file. You should use uv add when you want to formally add a dependency to your project.

Changing/Removing Dependencies

To remove a dependency you no longer need, use the uv remove command:

| |

This will remove requests from your pyproject.toml, update the uv.lock file, and uninstall the package from your virtual environment.

To change a dependency version, you can directly edit the pyproject.toml file. For example, to constrain numpy to an older version:

| |

After saving the file, your environment is now out-of-sync. You can update it by running:

| |

This command will read the pyproject.toml, resolve the new dependencies, update uv.lock, and ensure your .venv perfectly matches the new requirements.

Managing Python Versions

Unlike conda, uv does not manage Python installations itself. It uses Python interpreters that are already available on your system. You can install different Python versions using tools like pyenv, Rye, or the official installers from python.org.

You can see which Python interpreters uv can find with:

| |

When you initialize a project with uv init, it creates a .python-version file (e.g., containing 3.12). This file, along with the requires-python field in pyproject.toml, tells uv which Python version to use for this specific project.

If you need to create an environment with a specific Python version, you can use the -p or --python flag:

| |

This separation of concerns is powerful: use a dedicated tool (like pyenv) for managing Python installations, and use uv for managing project environments and dependencies.

Locking and Syncing

This is the core concept that makes the uv-style workflow robust and reproducible.

Locking (

uv lock): A lock file (uv.lock) is a snapshot of the exact versions of every package in your project’s dependency tree for a specific platform. When you runuv add,uv remove, oruv lock,uvcalculates all dependencies based onpyproject.tomland writes them intouv.lock. Committing this file to your version control (e.g., Git) ensures that every developer on your team, as well as your deployment servers, can recreate the exact same environment.Syncing (

uv sync): Theuv synccommand is the enforcer. It reads theuv.lockfile and makes your local virtual environment (.venv) an exact mirror of it.- It installs any missing packages.

- It removes any packages that are present in your environment but not in the lock file.

- It ensures every package is at the exact version specified in the lock file.

This workflow guarantees consistency and eliminates “it works on my machine” problems. The typical developer workflow becomes:

- Clone the repo:

git clone ... - Create the environment:

uv venv - Sync dependencies:

uv sync - Activate and work:

source .venv/bin/activate

When dependencies change, the process is just as simple:

- Pull changes:

git pull(this updatespyproject.tomlanduv.lock) - Re-sync:

uv sync

Your environment is now perfectly up-to-date with the project’s requirements.